Harvey,

Regardless of how long it had taken, I’ve chosen to concede the notion that any relevant dimensional ministry of and beneath my own would properly distribute the discovery of non-planar surfaces, and that the consequences of attempting to reverse so would be dire to the one who tries. However you felt about the possibility of the tesseract, you’d agree the n-dimensional mind has a non-wavering basic state that universally prohibits itself from even considering the higher spaces which it cannot experience; for I know it more than most. I had never intended to reveal to anyone the proofs you passed on to me, yet my Ministry learned of our relationship. Your rudimentary outline for tracking statistics in your own game inspired me to replicate the same process for my own; however, the prospect of the two-dimensional mind being able to expand itself so far was only attainable at a higher state. Namely, the monarchy has officials in every corner, and my attempt to incorporate tracking data triggered a worldwide alarm that an individual who hadn’t sworn secrecy was even minorly aware of the Sphere.

Years have passed since I began to wonder how this “epidemic” would conclude, and I’m sure even more will pass before I’m any more aware. I’ve attached the following documents as a reference for why the concept of your branch of tracking statistics should be released to the public, and how my story may be of relevance to your own futures.

Best regards

- I Accidentally Invent Basketball

Picture the three-dimensional depiction of a tesseract: a singular cube within a larger cube with its corresponding corners attached with slanted lines. Given the fourth spatial dimension can be represented on a surface two dimensions below its own nature, then imagine the ease with which I was able to visualize the third spatial dimension. I had no intention of discovering a non-planar surface that could exist outside of my own world, for it was an inadvertent finding. It was a result of my stint as a senior analytical researcher for the aggregate National Ringball League (NRL). It may seem an unfamiliar sport, although you’re likely more acquainted with it than originally thought to be.

Ringball is to my world as “basketball” is to yours. Similarities include teams of roughly thirteen players, five on the court at a time, in a sport demanding high levels of agility and athleticism. The goal of an individual possession is to “score” the ball (known colloquially as a “ringball”) into a circular enclosure known as the “ring” (what you would refer to as a “hoop”). The limitations of the world made it so that actions in basketball like dribbling are non-factors, which in turn eliminates the need to check for carries and travels. The most obstructed aspect of ringball is the “shot,” or how players score for their team. Since no one can jump, field-goal attempts are analogous to “bowling,” with the ring acting as the single pin and defenders working against the shooter to prevent the shot from going in. Otherwise, ringball and basketball are nearly identical.

I’d spent my early years in the workforce as an apprentice to Greg Richards: the original analytical pioneer in ringball, the first to ever track the tabular summaries of games, which supposedly encompassed the entirety of notable actions from a player in points, field goals, rebounds, assists, and turnovers. The world was captivated by Richards’s implementation of a smarter, savvier method to evaluate players, and he eventually became the sport’s most revered figure. My apprenticeship was earned largely in part to tracking hundreds of tabular summaries by hand, and including the differences between rebounds grabbed on offense and defense for the last fifty or so. I’d long suspected the hindrances of then-current techniques due to Richards’s discreetly operating for the Constitutional Monarchy and his hesitance in our time.

As Richards took me under his wing, he’d led me to believe the nature of his titles as “consultant” was unequivocally true. His reputation and public image were perfectly-rational and justified reasons for Richards’s undertaking of the position for which he pledged to perform his best in properly distributing the relevant information on the league’s players and teams. However, as I began to understand the nature of my apprenticeship which was largely of face value, I discovered Richards’s relation to the Constitutional Monarchy: for a strangely ambiguous and unknown reason, he’d been assigned a direct pipeline to our Constitutional Monarchy which acts as the sole governing body of my world. Although I may have been a fool to overestimate the value of a studentship under a man whom I’d seemed to surpass in analytical intellect, I hadn’t been unjust to question the meaning of the pipeline.

I was of such skepticism that I asked Richards why he needed a direct line to the world’s most powerful institution, to which he responded with a thought along the lines of how ringball’s growing analytical techniques were of higher mathematical quality than any other field, and how a strong relationship with a man of his significance related to the subject would benefit the intelligence of the world. As a practitioner of ringball analytics, even I was taken back when hearing the degree to which the monarchy valued its significance. I conceded the potential reason for how the conceptual integrity of the field could provide an alternative solution to another, although I’d grown to consider the creation of the tabular summary and its future additions to be rudimentary and simple relative to the potential the field held. I’d certainly pondered the growth of the field; nay, mathematics in general, and how it may extend past its geometrical limits.

I’d had spurts of true skepticism from time to time since my discovery of the relation between Richards and the monarchy; for although his reasoning was certainly and potentially valid, a strong inkling of seeming coldness traveled through my veins as the prospects of its true nature passed through my mind. I found myself having another sleepless night due to my growing distresses, and chose to travel down to a team’s arena Richards had given me a key to for the fifth anniversary of the date since the mentorship had begun. My recurring thoughts came as I set sight on the ring from the midcourt line for a numbered time I could no longer count. NRL ringball had been played for more than twenty years at the time, yet the most efficient scorers scored a mere twenty percent of their attempts. As the primary basketball fanatics you are, imagine the difficulty of scoring the ball in that sport if all five defenders were capable of levitating to the level of the net.

Mean shooting percentages would decline to historical lows and raw defensive efficiencies would rank as highly as they had ever been. Take the example of the 1963-64 season of my game, the last in which I was employed by the NRL. The average number of field-goal attempts for one team was 8,000 shots, and 1,064 of those attempts were made, which resulted in a mean conversion rate of 13.3%. The corresponding season in the National Basketball Association, as I’d later learn, saw the same figure at 43.3%. Basketball’s offenses haven’t yet understood the importance of shooting arcs, mostly because they don’t have the relative comparison of ringball as I did the inverse. Despite the norms of the sport and a general acceptance of low percentages, the number of analysts attempting to uncover a more efficient shot was pitifully low.

As I stood in the middle of the floor, I reminisced on my original observations on the art of scoring in ringball, down to its bare essentials. Well, the only way a shot can be made is if it travels across the court at just the right speed and angle to outmaneuver the efforts of its defenders. Theoretically speaking, the optimal way to reform the inefficient field-goal would be to alter the path of the shot itself. However, there were no practical means to establishing, say, a new direction of… and that is where I stopped myself. Let’s tinker, I thought. I’ve already come all the way here. If I were to take a shot in a new direction, how would that be? Clearly, there were inherent physical limitations to the practicality of the exercise. If I were to make use of a new direction, how would I know “where” it would be and how to angle my shot? I proceeded to seek a blank piece of paper that would eventually destroy the world.

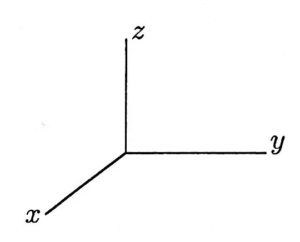

How did I arrive at the arena? I asked myself. The route taken to the stadium from my house was roughly five miles southward. How did I move to the half-court line from the main entrance? I moved roughly thirty meters eastward. I had drawn two perpendicular vertices, each on their own planar surface, an image that was of no initial significance. It was simply a representation of the directions in which I had traveled to arrive at the midcourt from the entrance of my home. They were the two paths of travel. But if another were to exist, I had expected an additional third would follow an apparent dimensional trend: the new direction would be perpendicular to its predecessors. As is with every case of exploratory research, I had encountered an immovable obstacle: there could be no perpendicular direction to the two-dimensional axis, as no added line would ever maintain a ninety-degree angle to either of its companions.

A trend had been clearly identified, yet the physical limitations of the world halted further progress. I had lost focus on numerous initiatives due to their practical inabilities, whether it be for methodological or technological blocks, which meant the prospect of warping the entirety of the world was an obstacle that could not be conquered. Failure was far more than an acquaintance to me, a natural stage of analytical development, so I had then felt no regret in not seeking an alternative solution, for the situation seemed far too impractical and outlandish and impossible to even begin with. I left the stadium and went to sleep, supposing any considerable revelation would be made during a more non-strenuous task. It was a practice I had adopted as a result of conceiving the offensive versus defensive rebounding splits as my mind was descending into a deep sleep, seeming premeditated strikes.

Even a moderate sleep was able to trigger the fitting conception. I maneuvered through a string of memories in my sleep and found myself back at the arena, positioned at the midcourt once again. The paper was in its original place with its original drawing gracing the surface. Regaining the same rudimentary state of mind I had when first conceiving of the third dimension, I called forth one conclusion I had already made in my subconscious: the paper maintained the qualities of a dimensional reality in which I was occupied, meaning its normal surface wouldn’t provide a direct representation of the third dimension. I had to treat a two-dimensional depiction of a third dimension abstractly compared to the surface I had available to me. It was then when the constant string of metaphysical concepts drew forth a new form of perpendicularity: one with its directions not only perpendicular to each other, but to the original surface itself.

The rest of the work was fairly simple, as three-dimensional inhabitants came to represent the fourth and further dimensions on even surfaces of only two dimensions. With the world’s intellectual commencing of the third dimension, I returned to the original prospect of a new ringball shot. Assuming utilization of the higher dimension, the ball would travel “overhead” relative to defenders and descend to the ring, following a trajectory similar to the path of an attempt in basketball. If it were able to be implemented into ringball, it would not only eliminate the inefficient mechanics of the traditional shot, but it would alter the normal positioning of defenses to an unknown “height” relative to the ring. The hypothetical third-dimensional reality would create a version of the sport more beneficial to offenses but a whole new one on its own, one that would coincidentally turn out to be your “basketball.” That, in layman’s terms, is how I accidentally invented basketball.

- I Meet an Invisible Stranger

“What are you doing here at…” Richards said as he looks at his watch. “…nine in the morning?”

“You have to see this!” I quickly revealed as I welcomed myself into his home. I uncovered the sheet of paper, now bruised and crinkly from when I had rushed to leave for Richards’s, and set it on his dining floor. “The entirety of ringball, nay, the world could be changed by this. Look!”

Richards, having clearly woken from a deep slumber merely minutes ago, gave a dazed glance at the paper as he walked toward me. “Give me a minute,” he said as he rubbed his eyes. Richards picked up the sheet and held it to his face, squinting his eyes as he read. As soon as he’d entered his gaze, he left it with an expression only justly recognized as one of pure irony. Richards turned to me with his look and asked, “What exactly is this?”

“I was considering the historical inefficiency of the field-goal attempt,” I said. “It could potentially be reformed to maximize offensive potential. Long story short, I outlined a theoretical third dimension. A shot within its boundaries are obviously out of reach, but I thought back to the time at which you revealed to me the nature of your connection to the monarchy. Wouldn’t the prospect of a third dimension with a reasonable framework be of importance?”

“Well…” Richards stumbled.

“Unless…” I began.

“No!” Richards intercepted. “Of course not… I’m a relative stranger to these concepts, although based on my previous knowledge, it looks promising.”

“Perfect,” I remarked. “Would you mind sending it to the monarchy for me? I haven’t the connections you do.”

“No,” Richards said in an alarmingly flat tone. He handed me the sheet back and walked me to his front door. “You can show it to them yourself.”

I soon found myself facing ten other individuals sitting on the other side of a long, stretched panel shaped like an arc rounded at the corners. I felt the eyes of the council’s stare at my skin, and with Richards’s firm-enough grasp to prevent me from exiting the room, I was seemingly deadlocked for a reason I had yet to realize. Richards walked me to a designated circle at the foot of the panel, after which the doors were promptly closed and he circled around to who appeared to be the chairperson. Richards met her periphery to exchange words, which left the chairperson no more discontented than she had seemed before.

“Nora,” Richards whispered to me as he made his way back to the entrance to the room.

The chairperson narrowed her gaze on me. “Mr. Richards tells me your claim to have diagrammed a third… dimension. Is this true?”

I had already started to sense the uncertainty of what appeared an emergency meeting, although the atmosphere wasn’t restricted to my end. “Yes ma’am.”

After a long pause, Nora follows with, “Explain it to me.”

I turned to Richards with what must have been a distinct look of confusion, to which he responded with a subtle gesture, Go ahead. “Well, I am currently an analyst for the NRL, which Mr. Richards may have mentioned. The current shooting techniques are very inefficient, so I outlined the possibility of a third hypothetical dimension in which a player could position the ball on a surface perpendicular to our current dimensional plane. Therefore, the ball would travel “overhead” and “fall” into the ring.”

Nora gave a puzzled expression, after which she responded with, “I don’t quite follow.”

Richards hinted for me to pass to her the sheet. “Right,” I said. “… the sheet.” Richards walked the paper to Nora, who gave a thorough review of the image until she saw it fit to resume the conversation.

“This was an… original conception?” Nora asked.

“Yes… ma’am,” I replied. ” Thought it up just this morning.”

With an unforgettable guise of dubiousness, Nora returned to her train of thought. “Have you possibly received any unplanned visitations in the past weeks?”

“No…?… ma’am,” I responded.

“I recommend, mister…?”

“I apologize, my name-“

“I recommend you seek deliberate conservation of this subject. I understand the circumstances of the situation, although you will simply have to consider the weight of my words in addition to the remaining council when I urge you to contain this from the general population.”

I was strongly taken aback by Nora’s remark. I feigned a look of concern to Richards which was followed by mild humored confusion. “I’m sorry, what?” I responded. “I was told by Mr. Richards that the monarchy would benefit from the use of the techniques used in ringball; and when I’ve chosen to come forth with what may be the most significant of all, you don’t want to inform the rest of the world?”

“That is correct,” Nora replied.

“Why?” I questioned.

Nora had already started to head toward the back of the room, at which point she turned a glance in my direction. “It is only for the betterment of mankind that you would not outlast your… convenience.”

Richards started to walk me out of the room, and said with a sympathetic tone of truth: “Trust me, kid. If I did not know this was in your best interest, I wouldn’t suggest you comply.”

I turned back to the panel, watching the council members make their way to ten different exits, one each seemingly assigned to one designated spot. I tried to catch a glimpse of Nora’s expression one last time, for the situation seemed far too surreal to have made a reasonable conclusion on its meaning at that time, but Richards urged me southward.

The ordeal was a firm nail in the coffin to assure me of the practicality of the third dimension, that it truly existed beyond the scope of my existing universe. However, I was compelled to believe the words of my mentor. He’d feigned looks of certainty the entire meeting, yet his final sentiments conveyed a sense of truth that I could not deny. I had not felt a particularly strong or emotional connection to the higher dimension, nor had its original purpose to vitalize the ringball shot signified any importance beyond its theoretical qualities, which allowed me to subside that entire day within the fortnight. My belief in three-dimensional realities had increased, but its relative insignificance was enough to keep my mind content.

I spent the next two years of my life as I had spent the previous two: not in a bore, per se, given my independent discovery of the third dimension. However, the finding wasn’t of use in my daily life, so I continued with the former as if the unveiling of depth were a mere concept that had not been proven, which it was at the time. It wasn’t until I was greeted by an invisible stranger when I chose to further pursue the third dimension. I returned to the arena well past midnight, as I had when first conceptualizing the new ringball shot, and was subsequently introduced to the strangest stranger I had yet to meet. He stood at the ominous midcourt line, facing the eastside ring, seemingly unaware of my presence.

“Excuse me?” I asked.

The stranger turned to face me with earnest eyes.

“How did you get in here?” I followed with.

After a prolonged silence, as quickly as he had materialized, he disappeared. I fell backward for a short moment, astonished. A second later, he reappeared in the same spot. I had started to suspect the late-night tiredness had begun to assume my mind, but as the man started to move toward me, he spoke.

“You were right.”

“Right about what?” I responded.

The stranger paused. “I just… took a jump. Care to take a gander as to what that means?”

I instantly flashed back to the meeting with the monarchy, with the entirety of the council members sitting at their panel, and how the chairperson “Nora” veiled a subtle threat on what I interpreted to be either my freedom or my life. If I were “right” on the matter of a subject concerning a stranger, one to show himself in a heavily secured professional arena with definitive language on a very vague premise, it would certainly have to be related to my discovery of a third dimension. This conclusion was enough for me to recognize the possible connection the stranger held to a three-dimensional world, so I laid out my initial framework.

“I couldn’t see you for a whole… second?” I began. “I can only presume you’re here on the matter of an extra-dimensional reality. Therefore, my lack of sight in that particular moment must be related to one of the qualities of the third dimension, for I would know if there existed cloaking or invisibility devices… If a two-dimensional being were to set his eyes on one of three dimensions, I would expect the dimensional structure of the viewer, that being the being of two dimensions, would have a physical hindrance with two-dimensional eyes, thus not being able to witness movement on the third-dimensional axis. That means… your jumping is movement in height?”

The stranger held my gaze for a quiet moment and then released his tension. “Thank goodness, I got the right guy! Do you know how many times I have gotten it wrong? Evidently, just look at your world right now.”

“Where do you come from?” I asked. “What are you doing here.”

“Do your people not greet their guests?” the stranger replied. “Anyways, my name is Harvey. I come from a place just outside a land called… New England. Do you know where that is?”

“No,” I quickly responded. Harvey conveyed a look of suspense, and I called on his social cue. “My name is Tom.”

“Alright, Tom,” said Harvey, as he walked closer toward the exit. “Let’s get out of here.”

“Well, where are we-” I started until I felt an inescapable wave of tiredness and was forced into sleep. I immediately regained consciousness in a new body. I felt stretched as though I had not known the feeling, which I hadn’t. My initial reaction was to look in a direction I’d never had the ability to observe before. Above me was an infinite expanse of black sky dotted with luminous points that radiated waves I could only interpret as not two-dimensional. I turned my head south and saw a shaded field of cultivated land that extended nearly as far as the horizon. As I noted the point at which the sky met the earth, a curvature was clearly visible. I had seemed to enter the three-dimensional reality, one in which the world was round. Then I realized I was effectively flying.

I turned to my left and saw Harvey, floating as calmly as could be, lighting a cigarette in the middle of the sky. He caught my glimpse and frantically put the lighter back into his pocket.

“Sorry kid,” Harvey recompensed. “You were out for a little while. Had to stay entertained somehow.”

“Okay, wow!” I smiled. I couldn’t refrain from feeling joyous, being able to fully experience the third dimension likely for the first time ever among beings of lower-dimensional realities. I realized the improbability of the event. “How exactly am I, er… seeing this?”

Harvey let out a puff of smoke from nearly-pursed lips. “Android,” he replied.

I let out a justifiable laugh. “Whatever that may be, why is it identical to my actual body?” I asked.

“Don’t want to ask too many questions, kid,” Harvey responded. “I’ll do the talking now, alright?”

“Sure,” I said.

Harvey spun the lighter on his finger. “You are seeing into our third dimension right now; which, congratulations on discovering by the way. I assumed it was you based on what I was able to see during your ‘meeting.’”

I pointed at him. “You were there?”

“Yes.”

“How?”

“Less talking, kid!” Harvey exclaimed. After he settled down, he gave a light-hearted shrug. “All of you fools can be further fooled when I jump up and down over and over again. None of you can see a thing!”

“Huh…” I marveled. Perhaps Harvey was a questionable character, and the surface details of his plan seemed as funky as any, but he had managed to infiltrate a world government regardless.

“I… am here…” Harvey stated as he retrieved an apple from his other pocket and took an awkwardly-long bite. “… because you did not one, but two, things. Well, you are one thing and you did another, whatever… You’re a… ringball analyst, correct? That’s what they call it? Our equivalent is called basketball, the shot trajectories for which you properly conceptualized, and coincidentally discovered the possibility of a third dimension. That’s what you are as well as what you did.”

“Er,” I mumbled. “That is correct, but… why take me out here and show me all this?”

“… As I’m sure you’ve managed to put the pieces together.” Harvey took a very passionate bite out of his apple. “Oh yeah…” he continued with his eyes set on the apple, transfixed, with a world-class grin on his face. “Whoops, sorry kid.” Harvey snapped back into reality. “Anyways, you’ve probably figured out that your world is full of degenerates and hypocrites.”

“Well, thanks…?” I replied.

Harvey’s eyes widened, clearly worried I had assumed the wrong impression. “No, no, no, not you kid. You’ve got some stuff up there, you know? However, the majority of your world reflects its dimensions. Exempli gratia… wait, can you read Latin? Nevermind that. A two-dimensional being usually has a two-dimensional mind. It’s not that they can’t comprehend a third dimension, per se; rather they choose not to. You, my friend…” Harvey pointed at my chest. “… are the exception, which means I have something important to tell you.”

“I mean, okay,” I replied. “You’ve just insulted everyone I’ve ever known and loved, but okay. What is this ever-so-important piece of information you have for me?”

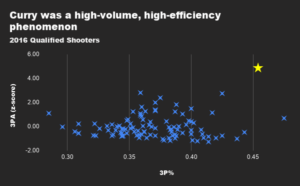

“Don’t get sassy with me, kid!” Harvey shouted, pointing his now ominous finger at my neck. “But anyway, I’ve hit a lucky streak with my work. I’m a basketball analyst, you see, basically the same job as yours just with a shot in three dimensions rather than two. So, the one you conceptualized. I’m sure you’re a skeptic of the… what do they call it, tabular summary?”

“Yeah, partly,” I said.

Harvey paused. “That’s really what you call it? Whatever. Anyway, we call it the “box score” here on Earth. We’ve got a few more stats we track, like steals, blocks, fouls… I’m surprised you hadn’t further questioned that Richards guy on why none of you track defensive stats.”

“I mean, I have asked him before,” I said. “It just never received any serious consideration.”

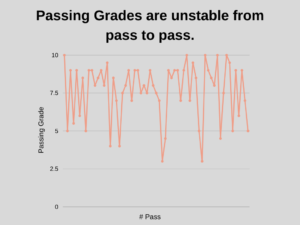

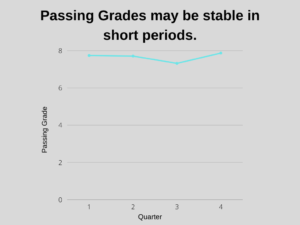

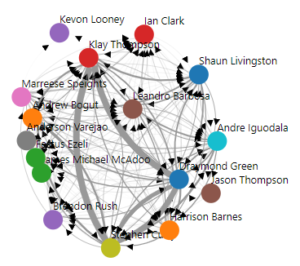

“Regardless,” Harvey said. “Perhaps you’ve had an inkling of this, but the box score… I’m just going to call it the box score from now on, okay? The box score is a poor indicator of how good a player is, which you may have picked up on. I created a new type of tracking statistic with a premise I think you’d find mildly intriguing.”

“Okay, shoot,” I replied.

“I’ll begin with a question… What’s the point of having a player on one of your ringball teams?”

“Excuse me?”

“Come on! If it’s such a basic question, you’ve got to know!”

“Well…” I said. “Players are acquired and signed to improve their team. That’s a part of my job: choosing between players.”

“See!” Harvey marveled. “I knew you weren’t a lost cause! Alright, second question: define a team’s success.” He took another massive bite from his nearly-finished apple.

I granted a fairly clear answer. “The most basic form of success is winning games,” said I.

“Correct again,” Harvey replied. “Next question: how do you win games?”

“By outscoring your opponent,” I said.

“Outstanding!” Harvey exclaimed. “Now that the premise is laid out, I’ll ask you one final question: wouldn’t it make logical sense to therefore say the best player or players have the most positive impacts on the scoreboard? Say, their team’s point differential?”

I had never considered nor conceived the approach Harvey was taking. It was excessively simple yet undeniably true. If you broke either my or his game down to its most rudimentary qualities, he was correct. For what did I know up to that point? It should have been fairly obvious there was no definitive value to an assist, a rebound, or a turnover. However, my two-dimensional mind was likely incapable of constructing the logic in the first place, I’m willing to admit.

“You’re right,” I replied. “I’d never thought of it similarly, but it’s correct. If you’re truly after team success in the player selection process, you should use your framework.”

“The best part isn’t even the idea,” Harvey said with a mouth full of a sandwich that reeked of tuna. “That tracking metric I mentioned, it relates the difference of his team’s points to his opponents when a given player is on the floor. But we use something called pace adjustments… normalize it all to a hundred possessions. When Jimmy John is on the court for twenty possessions and his team outscored its opponent by one point, Jimmy has a plus/minus of five. The name is still in the works, may have borrowed it from hockey. Don’t ask what hockey is.”

“Interesting concept,” I replied. “I agree with the premise, but there’s one last detail you’ve left out.”

“That being..?”

“What role do I play in it?”

“Excuse me?”

“You seemed to have, what, drugged me? You took me to an extra-dimensional land and revealed the most hidden secret in the whole world to… tell me about a basketball stat?”

“Right! Nearly forgot,” Harvey said, his hands fumbling the sandwich as he rushed to finish his sentences. “I need you to get back into another meeting with your monarchy.”

I initially refused to accept the truth in his request, that it was more likely to merely another one of his one-liners. “Okay… no,” I replied. “But even if I were to, how and why?”

“You’d have to do or say something to draw their workers out, snatch their attention. Once you do that, you get in a meeting with them, reveal a mildly concerning piece of information that suggests one of their citizens is getting close to conclusive proof of the third dimension, which would hopefully reverse some of the backfire effects in the majority of your population.”

“Again… no,” I said. “The last trip I would want to take is back to that council. Do you not remember their poorly-concealed threats?”

“I won’t sugarcoat it, kid,” Harvey said. He took a butter knife and a jar of peanut butter from his coat pocket and opened the top end of his sandwich, slowly spreading a new layer onto the remaining spinach and tuna. “It would definitely be a risk. Of course, to take one like that, you’d need a reason.”

“Indeed, I would,” I remarked.

“Anyways,” Harvey continued. “As I was saying, your people are… set in their ways. If you provide them with contradictory evidence to a long-held belief, their minds short-circuit. They don’t know how to react. Therefore, if you want to break that streak, you’ll need to snap them out of it. Wouldn’t you want that?”

“Ideally, yes,” I replied. “But not enough to risk my life for it.”

“Tommy, Tommy, Tommy!” Harvey said. “If we can pull this off just right, the entire… well, your entire word will reform. There’s no real reason to ignore the realities that exist beyond their own at this point, is there?”

I pondered his explanation. There certainly existed a strong hindrance in the minds of my people up until then, and to reverse the effects would take one of the largest efforts known the mankind. However, I considered the odds an opportunity to do so would ever appear again. Given the parameters of my own situation, it would take another rediscovery of the third dimension, which may not happen for hundreds or thousands of years, or ever. If I were to involve myself in Harvey’s ordeal, the pretense to enter the council would have to be airtight.

“If… I agree,” I proposed. “… what are the terms?”

“Well, I was thinking the safest option would be the metric I call Plus/Minus. Slip the idea to Richards as if it were your own. Obviously, the metric isn’t something anyone in your world could freely invent, so it would raise enough suspicion to lead to another meeting, but not enough to conclusively prove your connection to the third dimension… The real one, not the conceptual one.”

“Okay,” I considered. “No.”

“Come on, kid! Do you know who we’d be taking down here?”

“No, but please tell me.”

“They’re known as the Monarchical Establishment for the Detainment of Interdicted Apprehensions. How does that sound to you?”

“It sounds like someone was eager to spell ‘MEDIA.’”

“Alright kid… Are you in or not? I’m nearly done with all the meals I packed.”

My mind returned to the hesitance of Richards, the demeanor and nature of the monarchy, and the limitations of even myself that I wanted to expand. “I’ll do it,” I replied. “I’m in. But before I make a firm commitment, I need you to acknowledge something for me.”

“Okay, Tom,” Harvey replied, with strong relief in his eyes. “What would that be?”

“You explain to me that my people have a certain ignorance of them. Whether it’s due to their two-dimensional reality or their own chosen limitations, it is there. However, couldn’t the same be said for all beings?”

“I’m not following,” Harvey responded.

“Harvey, do you believe in a fourth dimension?” I asked.

“Alright, kid. Where are you getting at?”

“What do you call a three-dimensional square?”

“Cube.”

“What would you call a four-dimensional cube?”

“Well, there was one guy several decades ago… Hinton. He used to call one of those a ‘tesseract.’”

“Do you believe it exists? The tesseract?”

“Now you’re just grasping at straws, kid.”

“If you can’t display a mindset beyond that of my own people, ignoring the absolute advantage you have of living in a three-dimensional world and rather look at the matter relatively, how am I to believe you’re any better than those we are supposedly against?”

“If a fourth dimension truly existed, I’d know. My world would know.”

“How?” I asked. “My people would never have discovered the true third if someone, being you, hadn’t been able to confirm it for us. There could be an infinite number of dimensions in theory, yet you deny the existence of any past a third because you simply can’t see it?”

“Consider my offer,” Harvey concluded before he took a remote from his left pocket, pointed it at my head, and clicked.

- I Accidentally Destroy the World

I woke up in my previous body, detached from the machine Harvey had used to allow me to see the third dimension. Despite not possessing the spherical eyes I had previously, I could still picture depth and height in my brain. The last statements Harvey left me with were not of my highest agreement, but one sentiment he gave remained in my mind: that my world is not incapable of seeing more, they choose not to.

The next day, I went to Richards’s office and discussed the potential of relating a player’s impact to his team’s point differential, and even spun my own ideas of how to improve the metric: methods to further isolate the value and forming more conclusive coefficient estimates. Richards conveyed the same look of doubt he had two years previous and told me it was an issue the monarchy was more fitted for. Perhaps he should have expected more restraint on my end or resistance to seeing Nora and the council members again, but my feigned looks of concern were enough to convince him I hadn’t expected a second visit.

I found myself back in the same room with the same individuals, each in the same positions and for the same purpose: to detain my learning of any further knowledge. Richards repeated his earlier act of informing Nora of my finding, likely how its complexity is beyond reason for a “two-dimensional” mind. I was certain the monarchy was aware of the third dimension, and they proceeded exactly as Harvey suggested. All the members were settled in their designated circles, Richards circled back around to me, and the second meeting began.

“Mr. Evans, I won’t dance around the issue at hand. I’ll give you the complete details of what we know. Is that alright with you?” asked Nora.

“Yes ma’am,” I said.

“We know you’ve been contacting a being of the third dimension. We don’t know whom or why, but we know he is of a higher reality.”

My lungs felt as though they had frozen over. I found myself struggling to breathe, hyper-aware of the sounds of my exhalations. I had never been in an interrogatory setting before. Perhaps it was my inexperience, my surprise, or my lack of faith in the ideals Harvey was insistent upon, but I found it nearly impossible to continue and keep up the charade.

“How would you know that, ma’am?” I cautiously asked.

“There were more than twelve people in the first meeting, Mr. Evans,” Nora replied. “A man was seen disappearing and reappearing during the entirety of the congregation, although he was remarkably quiet… Regardless, your idea of the third dimension and this invisible man were enough to confirm you had either already been contacted or would be contacted by the individual. Would you confirm this story?”

Given the details of Nora’s story, it’s clear the monarchy had no conclusive proof of my communication with Harvey, despite their placing him at the proper location and the ability to reasonably presume a connection between us. The legalities of the matter would have prohibited me from any rightful imprisonment, given the act would break the world’s laws, although Harvey’s disdain of the two-dimensional mind led me to believe the lawfulness of the situation wouldn’t concern the monarchy. They would eliminate the chance of my spreading the proof of a third dimension in any manner, lawful or not.

The unspoken truth between the council and I agreed the both of us was aware of my knowledge; but with the hint of uncertainty I was granted, I made the quick decision to swallow any pride relating to the government’s treatment of its people and chose the more secure, more legal route. “No, I can not, ma’am.”

Nora transitioned between expressions of frustration and amusement in the seconds following my statement, her jaw trembling with eyes of sharpened disdain. She cued to Richards, the latter of whom released his grasp on me. Thank Harvey, the largest improvisation of my life had managed to do the trick. Although the air whispered the truth that Nora and the council were fully aware of my connection to Harvey, they were not willing to act on any of the precautionary measures they may have planned on implementing; at least, not until a later date. I saw myself out of the council, turning back one last time to replicate Harvey’s apple smile directed to Nora. I did not even need to hold her gaze to feel her anger from tens of meters away.

I returned to my home in mild exhaustion: a tired and unprocessed mind from the events of the previous mind along with slight bodily fatigue from the day. However, I felt a strong sense of accomplishment and optimism. As Harvey had managed to infiltrate the government, I had managed to debilitate its intuition, use their own logistics against them. I was not naïve either; I had already expected further action from the monarchy, but the protection of the law was enough to ease my mind in the evening. I felt a strong hesitance to sleep early, however, likely due to having entered another dimension the last time I’d slumbered. The controlling factor was the plan I had unconsciously formed in the preceding hours: to spark a widespread belief in a dimension of three axes.

Although mine was no household name, I had built a formidable reputation for myself as one of the world’s leading ringball analysts and mathematicians, the reasons for which I would make occasional appearances on the leading sports network: the Entertainment and Sports Broadcasting Network, or ESBN, to discuss the league’s bright, new players or take a deeper examination of my analyses. I concluded the most effective way to spread the word of an extra-dimensional world was to break the script in my nearest scheduled slot, that in the following fortnight. I had figured the two-week period would lightly settle the minds of the council, to perhaps suggest I would not take any immediate action. Additionally, the duration would ensure the monarchy would not have the necessary time to plot to potentially retrieve me from mainstream society.

Promptly, I found myself facing augmented light sets and cameras at the end of the waiting period. The introductory message to my appearance began, although I wasn’t truly listening, after which the cameramen angled their device in my direction. I took a silent pause and proceeded to commence the speech I had spent the previous two weeks drafting. I briefly remember my words on conceptualizing the third dimension, my first meeting with the world monarchy, and a segment of my mid-flight conversation with Harvey. The last trap I had not expected was the all-seeing status of the monarchy, for they truly had eyes and ears in all places. My last recollection of my time on the air was the sound of a dart, and my eyes went black.

—

I remained in a perpetual state of loose consciousness for the following weeks, with vague memories of my journey onto the train, aided by the careless hands of the monarchical workers, along with a more distinct image of Nora’s pleased face as I was thrown on board. There were deep, booming sounds of gravel and dirt escaping their previous bounds of the ground, entire oceans parting way for the massive, yet two-dimensional, absences of water. There were vague remarks as to how Harvey’s statistic could bleed the same fateful events into the three-dimensional world. I was mostly asleep the entirety of the week following my television revelation, but I’d learned enough: the world had imploded on itself, its people enraged by the government, others in support of it. I was never aware of the details, but it was clear military warfare became a heavy involvement.

If my world were three-dimensional, my waking image would have been a bronzed, steel wall providing the perfect view of a sky claimed by the ashes. My immediate reaction was not only the recognition that the plan had worked, for the world had been completely informed of the third dimension, but that the trade-off was an inescapable, inevitable series of destruction: another effect I had failed to anticipate. My next reaction was to absorb my surroundings. I had caught a mention of a train, one of which I was certainly on. The oxidized walls, the rusted bolts, it was a train that had been constructed some time ago. The air on the outside was certainly too polluted to safely breathe, which led me to contemplate my being there. I had thought, perhaps, my status as a threat had carried over, although the rest of the world knew what I knew. I like to believe it was due to my connection to Harvey, one that could potentially pose an even greater threat to the world order, one that could bleed into the higher dimensions.

Regardless of why, I found myself on the train. I could elaborate on the seven years of my life on it leading up to my current writing, but the commencing letter discloses all the necessary information. My world was more susceptible to its end more than Harvey’s, whose publications could potentially provide the same reform to his world that he promised mine. I mentioned Harvey’s hesitance to accepting the tesseract, one that would certainly be amplified by the rest of his population. However, he had recognized the possibility, as did the rest of the Earth. As the train passes my once beloved stadium, I’ll pass this letter over, triggering what would likely be another of Harvey’s reappearances. For now, I’m bound to a train named for the skyline its viewers would endure for the remainder of their lives.