“Stephen Curry in 2016 is more fun than anything, maybe ever…” – SLATE

The greatest point guard of the century set the Bay Area into a Warriors frenzy with his electric three-point scoring and the team’s dynastical tendencies, with records being broken left and right. Curry’s season may have been highlighted by 402 three-pointers made and a unanimous MVP, but very few people knew how good he actually was that year, even those living in the eye of the storm. He entered rarefied air in his ’16 season, and no player since then has yet to match it. But exactly how good was he when he was drilling half-court shots seemingly at will? With Curry’s evaluation, I’ll try to answer a long-thought question: was Curry’s 2016 campaign the greatest offensive season in league history?

Scoring

Curry’s scoring alone took Golden State’s offense to dynastical levels. During possessions in which he attempted to score, defined as either a true shooting attempt or a scoring turnover, the Warriors posted an offensive rating of 127. That was a whopping +21 relative offense, and there’s potent evidence behind a figure of such a magnitude.

Due to Curry’s historical outside shooting, his inside scoring received far less recognition despite being one of the skill’s best. Among players who played for more than a thousand minutes, Curry was thirteenth in field-goal percentage on drives; which, considering his 6’3″ stature, is geometrically more masterly. A part of Curry’s surprising prowess in the paint was his strength; according to CBSSports, he could deadlift 400 pounds in the summer of 2016, a mark no Warriors could top except for the 6’11”, 255-pound Festus Ezeli. Paired with a solid motor, Curry was able to penetrate defenses with relative ease.

He was a very prolific paint scorer, having taken 22.5% of his attempts from within three feet of the basket. With respect to Curry’s three-point barrages and smaller stature, his frequency was unexpectedly high. He was also able to capitalize on these high-efficient looks at a 69.6% clip, strikingly greater than the league-average of 62.4%. Curry would often opt for these shots to avoid double teams on the perimeter, swinging around the arc, and finding an angle to drive. His size and vertical leap alone weren’t enough to dominate defenses in the post, so during his forward-facing drives, Curry would either go take an early step to gain ground against the opponent or his premier center of gravity. Learning to take the toll of movement with his hips instead of his ankles truly unlocked Curry’s greatest interior capabilities.

The other component to his elite finishing was Curry’s ability to split defenses. As the greatest shooter ever, he also became the most gravitational player ever. He’d rarely not see multiple defenders in his periphery when operating on the perimeter, yet it was never destabilizing. If two defenders went on either side of Curry, he’d split their position with surprising quickness and agile lateral movement. The aforementioned utilization of his hips allowed him to change direction with fast pivots, which often left defenders in the dust. Curry was one of the league’s best paint finishers, and it was the weak point of his scoring résumé.

Everywhere outside the paint was Curry’s domain… not that the paint wasn’t already his in some form either. He stuffed the stat sheet with a collection of absurd shooting scores that paint an extremely flattering picture of Curry’s outside scoring, a strong point of which was how he and his teammates set up his scoring. Curry was one of the most efficient catch-and-shoot scorers in the league that year (68.6 eFG%), only behind J.J. Redick for players who took more than 400 catch-and-shot field-goal attempts. However, contrary to the traditional tendencies, Curry’s efficiency didn’t rapidly decline on non-assisted attempts. He was the league-leader in effective field goal percentage on pull-up shooting (61.9%) for players with more than nineteen attempts. For reference, Curry took 687 of these attempts. The next most-efficient player to even take one hundred, D.J. Augustin, shot 54.3%.

Curry wasn’t an “opportunist,” as many primarily catch-and-shoot scorers are. He was a master schemer, consistently creating his own shot while also being an elite catch-and-shoot scorer. 37% of Curry’s two-point field-goals were of teammate assists, significantly lower than the league-average of 51%. From three-point range, his figure is 55%, a large decrease from the league-average of 84%. It’s probable Curry’s scoring would’ve been more scrutinized if he were the product of a system in which he was set up for high-quality attempts by teammates more than himself, although this wasn’t the case. Curry’s status as an offensive engine wasn’t exactly in question, but the rates at which he creates his own field-goals further the idea that he was a peak offensive player during his second MVP season.

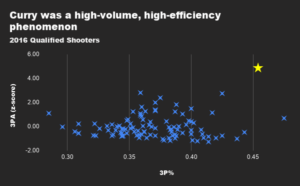

No player has yet to match the historical contributions of Steph Curry’s outside scoring. He attempted a mind-boggling 886 three-point shots during his 79 games played, nearly 230 more shots than the second-place finisher in the stat (James Harden). Curry was surprisingly second in efficiency (45.4%), trailing only behind the Clippers’ J.J. Redick. However, Curry attempted more than double of Redick’s shots on far greater self-reliance, which suggests from an all-things-considered outlook, Curry was the most efficient three-point shooter in the league. Using the league-average three-point percentage as a relative comparison, Curry added 265.8 net points to the scoreboard through his three-point attempts alone. The efficiency and volume at which he made three-point shots make Curry’s ’16 significant in league history as the greatest outside scoring season ever.

Yellow star denotes Curry

The Baby-Faced Assassin had not only the greatest scoring season of the year (leading the league in both scoring rate and true shooting percentage, as well as being the only player to ever win the scoring and efficiency titles) but the history of basketball. Curry leads the all-time leaderboard in Backpicks‘s ScoreVal metric as well as (in theory) my own of similar nature: Scorer Rating. Given the circumstances of his scoring, and how his greater self-dependence is an indicator that his scoring statistics are more reflective of his true abilities than the average “opportunist,” it’s fair to say Curry had the strongest scoring peak of any player in league history. As the thirty-first highest peak in relative true “scoring” percentage (which uses a scoring turnover) estimates as a scoring attempt and the eleventh-highest peak in scoring rate with historic frequency, Curry’s mix of volume and efficiency was unprecedented.

Off-Ball / Movement

The next trip up Curry’s sleeve, and a large contributor to his assisted shots, was his world-class movement without the ball in his hands. An overlooked skill when it comes to an elite offensive player, Curry’s not often recognized for it compared to his eye-popping distance shooting. Fortunately, he was able to put it to good use as a member of the Warriors, a team with some of the most dynamic ball movement ever, comparable to the ’96 Chicago Bulls. Curry was a threat all over the court without the ball, keeping defenders on their toes with his presence alone.

With the point guard duties he had, Curry would often start his off-ball stints at the top of the perimeter. He would primarily target either the corners or the paint, two of his most efficient ranges. To do so, Curry would often make slow rotations to a corner and let his teammates go to town. These made up a lot of Curry’s “excluded” possessions, but his positioning in these spots was another outlet for shot creation. He’d sometimes feign a backdoor cut to unclog a lane in which a teammate could drive: phenomena that would occur either starting at a corner or up top. Significant credit for this is due to his creation instead of his off-ball capabilities, but the grace and effectiveness with which Curry could feign cuts was extraordinary.

Aside from his creation abilities off the ball, Curry’s movement itself rivals the all-time greats in the skill. He has a reputation for a game that doesn’t require the athleticism most do, but the quickness in his routes is a product of a strong physical foundation. The excess training of his hips provided an easier way for Curry to reposition himself on drives, otherwise known as changing direction. It’s how he gave a seasonal montage of possessions in which he was driving to the hoop and swiftly stepped back, showing an uncanny tendency to lose his defenders. Curry was by no means screen-reliant, but his ability to weave in and out of teammate screens and opponent setups was the boost he needed to improve his self-creation off the ball.

Playmaking

Even if Curry were a pedestrian scorer, his passing and creation would’ve kept him afloat as an offensive engine. The quality of his passing wasn’t the focal point of his playmaking, and the skill is accurately represented by his Passer Rating per Backpicks. Since his breakout ’13 campaign, the metric has graded him in the mid-to-high-sevens on the one-to-ten scale. A lot of his assists were products of his elite vision, which made him especially aware of the corners. With five teammates who shot higher than 40% on corner threes, a lot of these passes were tailored to Golden State’s roster. Curry was additionally proficient at splitting defenses with his quick bounce passes. A common trait among elite playmakers, he refined the tactic with his strong hips and vision approaching the hoop en route to his 1,261 points created through assists.

There wasn’t an excess number of negatives with Curry’s passing. The notable ones include his tendency to overpass against taller defenders. During games against elite defenses (especially the recurring January 15th matchup against the Spurs), he’d find himself picking the ball up early, forcing a pass into the post or out to the perimeter. Defenders like LaMarcus Aldridge and Kawhi Leonard rushed Curry into these passes, and his intentions were clear: to avoid the long arms of his defenders and skip a pass to an open teammate. However, Curry would often underestimate the launch angle of these passes, and they’d gain too much ground before their final descent. The same would occur with some of his full-court baseball passes. The main theme with Curry’s passing deficiencies was that he overestimated the necessary distances for tougher passes, but the lower frequency at which these happened made them minor issues.

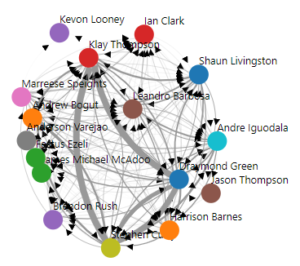

PBPStats – a condensed version of Golden State’s assist network

The Warriors were a movement-heavy team, having led the league in assists per 100 possessions by a significant margin (+2.6 assists), secondary assists, and assist points created. The nucleus of this action was made up of the team’s “big three” in Curry, Draymond Green, and Klay Thompson. Curry’s strongest link was with Thompson, to whom he assisted 209 field goals. He also assisted 139 of Green’s shots and 66 of Andrew Bogut’s. Based on the positioning of these players, it’s clear a lot of Curry’s playmaking was focused on or around the perimeter. He averaged 2.5 fewer assists per 100 possessions with his star on the arc, Thompson, off the floor. Curry’s playmaking was understated that year because of how many more shots he was taking (+3.5 more attempts per 100 from the previous season); but even then, his playmaking value was near the top of the league. Golden State’s passing and Curry’s efficient teammates counteract some of that deflation, but the confounding variables almost seem to cancel themselves out.

Defense

Curry is often criticized for his man-to-man abilities, and there’s some truth to that. He wasn’t the greatest at positioning himself, keeping a naturally flat-footed and unathletic stance. Curry had solid hands in these spots, covering higher and lower passing angles with either arm, although his 6’4″ wingspan made it slightly harder to effectively clog passing lanes.

Among his more potent errors include mispositioning; he’ll sometimes miss a matchup entirely, the only other main instance of this being a tradeoff of his good rebounding. Curry would often lose his man positioning himself for the defensive rebound. This does make it a bit of a gamble, but the generally-high defensive rebounding percentages among teams (league-average 76.2%) made it so that only a small percentage of possessions would see these fallbacks. But Curry was a surprisingly good rebounder for his height, having grabbed 4.9 defensive rebounds per 75 possessions at a 2.9% clip, suggesting it was the best defensive-rebounding season of his career.

Curry’s small frame made it hard for him to stay in front of stronger matchups, so he’d sometimes be left in the dust on defensive possessions (just as he did to the NBA’s very best defenders). Ironically, Curry was given a taste of his own medicine in these stints. He was similarly susceptible to screen action, fizzling his entire value out against stronger defenders by entirely losing his man. The strongest positive of his man-to-man game is his ability to maintain space with his matchup. Curry can string together good defensive possessions when his matchups are moving laterally, keeping close but safe gaps between them and himself. He also has half-decent hands, which allowed him to break up plays in and near the radius of his wingspan. His transition coverage and fallback play provided a lot of unseen value for the Warriors, keeping offensive matchups at bay and preventing an underestimated number of field-goal opportunities.

Impact metrics painted a consistent picture of Curry in which he was a positive defensive player. He was generally favored by more play-by-play infused and non-box metrics, with defensive scores higher than a point in PI RAPM (+1.7), PIPM (+1.47), and RAPTOR (+2.78). Although, box-oriented metrics showed him some love too, with a +1.6 score in the defensive component of Basketball-Reference‘s Box Plus/Minus model. The lowest of Curry’s defensive impact metrics was his single-year “luck-adjusted” RAPM (-0.07), which painted him as a minor negative. The aggregate of Curry’s scores suggest his defense was a clear positive to his team on the defensive end, and without any confounding variables to drastically alter the results, it’s fair to say impact metrics give strong portraits of him on that end.

Summary

With Curry’s evaluation under wraps, there’s now a fairer picture as to where his offense stands on the historical leaderboards. His world-class combination of scoring volume, efficiency, playmaking, and off-ball movement, paired with peak scalability, makes it hard to say his claim for the sport’s peak offensive season is rivaled by anyone not named Michael Jordan. Given the hindrances of Jordan’s impact from his more questionable portability, I’d deem Curry’s second MVP campaign as the greatest offensive season in league history. With his mild-positive defense in the equation, using my updated “Championship Probability Added” calculator, I’d estimate Curry would’ve provided a random team with a 10.2% increment to win the title. (Note: the percent increments will be significantly lower than previous evaluations because the calculation now considers impact on below-average teams.) His full-strength title odds would clock in at about 11.7%, which would rank as one of the fifteen best seasons of all-time.