Nowadays, you’re either an eye-test guy or stats guy, right? There seems to be no acceptable middle ground, especially to the side I’ll take a deep-dive into today, the “traditionalists.” The use of any intelligible statistic beyond the box score signals someone who skims a Basketball-Reference page to evaluate a player, a common notion set forth by some. I haven’t absorbed the entirety of the traditionalist standpoint; so, to gain insight on what it entails, I turned to Ekam Nagra, the face of the “Ball Don’t Stop” Instagram page, a platform he uses to host a podcast. He will often use his posts to share his ideas on how analytics are poor tools to evaluate players, at times to interview former and current NBA players with similar opinions.

Through my time spent learning the tendencies of his methods, I believe I’ve found a reasonable set of pillars that provide the structure for his evaluations, rankings, or any other process that requires player assessment:

- Because the rules of basketball dictate the value of a possession to rely on whether or not the ball is scored, the most valuable individual trait is also scoring.

- The previous view can be further defined to focus on volume scoring (although Nagra has expressed a distaste for the term in the past), with a crucial context of efficiency being the difficulty of the defensive scheming and the type of shot.

- Defense, on the player and team levels, is less of an individual quality than offense because the latter dictates the momentum on the defensive end (offense “creates” defense in a way).

- Statistics and analytics, in essence, lack context and are watered-down interpretations of court actions used as a flimsy replacement for “true” explanation.

- Lastly, basketball analysis is an esoteric field. It requires direct, firsthand experience as a competitive basketball athlete to attain a higher ability to comprehend game actions.

Anyone familiar with my previous work knows my evaluation tendencies, ones because of which Nagra would almost certainly dub me an “analytics boy” or a “stat fan.” I consistently use statistics and impact metrics in my end-of-season evaluations, so as a potential disclaimer, I am writing from a “progressive” perspective (i.e. in support of the analytics movement). Thus, I’ll dissect the meaning of Nagra’s explicit and implicit rationale to provide an analytical alternative, which will hopefully take the series an extra step further in the truer understanding of the psychology behind basketball.

Scoring Blindness

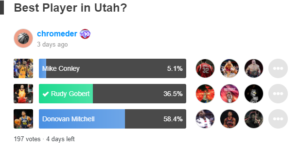

As I discussed in the first installment of the series, as defined by the Thinking Basketball book, “scoring blindness” is the tendency of a critic to overrate the contributions of a team’s highest-volume scorer (i.e. the player who leads his team in points per game). Although I don’t agree with the employment of such a method, I understand the concept behind it: if the point of a possession on offense is to score the basketball, then the best players will likely score most often. (This is something I generally agree with). However, Nagra takes it a step further in Episode 91 of the “Ball Don’t Stop” podcast, from which the following quote is derived:

“… It just drives me crazy when I hear this, and I laugh, and it’s usually people that never played basketball saying this, or people that never really scored when they did play basketball, saying, ‘Oh, he’s just a scorer.’ … ‘You know, he’s the best scorer, he’s not the best player.’ … Scoring isn’t everything in basketball, but I’ll be the first to tell you it is by far the main thing. The name of the game is getting buckets.” (Ekam Nagra – Episode 91 of the “Ball Don’t Stop” podcast)

I understand the train of thought behind Nagra’s beliefs. A team’s efficacy on offense is entirely dependent on how frequently they score the ball. This is why a team’s Offensive Rating is so widely used; it measures how good a team was at performing its offensive duties. Therefore, the “best” offensive players make the largest scoring contributions. However, I think it’s a misstep to connect scoring on the team level to individual scoring on the player level. This claim relies on the belief that individual scoring is not the only way to positively influence a team’s offense. High-level shot creation that unclogs the floor and opens more efficient attempts is, in fact, usually more effective to the team compared to consistent “hero-ball” and isolation possessions.

Scoring blindness is, as stated earlier, the propensity to rate players based on favorable points per game figures, and we see it in practice with the criteria Nagra uses the evaluate players:

“The number one thing in basketball, the foundation of the game is putting the ball in the basket. The guys that did that the best are the guys that shined the brightest in the history of the game. They’re the ones that moved arenas, they’re the ones that sold jerseys, they’re the ones put teams on their back, the guys that are, you know, making sh*t happen on the basketball court.” (Ekam Nagra – Episode 91 of the “Ball Don’t Stop” Podcast)

I’ll return to the tendency later, but Nagra consistently attributes questionable factors to a player’s “goodness,” such as the roar of the crowd, merchandising, and a touch of the “Lone Star Illusion” (the tendency to undervalue the effects of a supporting cast, another topic invoked by Thinking Basketball). A self-proclaimed former player, Nagra often relates the demanding environment of the NBA to street-ball or pick-up preferences:

“It’s… it’s simple, you know, common f*cking sense. If me and you were to walk into a court today and, er, open run or tryout or whatever, the first guy that would stand out, the first guy we’d look for if we were smart, is the guy that’s putting the ball in the hoop.” (Ekam Nagra – Episode 91 of the “Ball Don’t Stop” Podcast)

This reminds me of the mentality of middle or high-school roster selection, or the mindset of the young players, which pose the ultimate goal to be the best and brightest scorer. After all, almost everyone wanted to be the ones to hit the game winners and the clutch shots when they were young, and that means you would want to become the best scorer. As I dive deeper into Nagra’s evaluation style, I’ve become more convinced a lot of his rationale is based on his time as a player: who stood out and who appeared to be the best.

Nagra gives another opinion that provides insight on how he relates scoring to team performance later on in the episode used for the aforementioned quotes:

“But those teams that win, and these teams that are led, and teams that go far in the Playoffs, they’re the ones that have the best scorer on the floor… or the second-best scorer on the floor… at all times.” (Ekam Nagra – Episode 91 of the “Ball Don’t Stop” podcast)

Because he doesn’t give any specific examples, we could investigate this claim to create a “stepping-off” point to see whether or not his claims are based on facts or the internal, intuitive feelings he conveyed earlier in the episode. To either confirm or deny this claim, we can look at the league-leaders in points per game in recent history and connect them with which round their teams advanced to in the second season. (He doesn’t give a specific round or the number of postseason games played to constitute teams that “go far in the Playoffs,” so I’ll assume the lower fence is a conference championship appearance.)

If a (qualified) top-two finisher in points per game was on a team that advanced to the conference championship or further in the same season, he will receive a “Yes.” If a player’s team did not manage to reach the semi-finals, he will be denoted with a “No.”

- 2019-20: James Harden (No) and Bradley Beal (No)

- 2018-19: James Harden (No) and Paul George (No)

- 2017-18: James Harden (Yes) and Anthony Davis (No)

- 2016-17: Russell Westbrook (No) and James Harden (No)

- 2015-16: Stephen Curry (Yes) and James Harden (No)

- 2014-15: Russell Westbrook (No) and James Harden (Yes)

- 2013-14: Kevin Durant (Yes) and Carmelo Anthony (No)

- 2012-13: Carmelo Anthony (No) and Kevin Durant (No)

- 2011-12: Kevin Durant (Yes) and Kobe Bryant (No)

- 2010-11: Kevin Durant (Yes) and LeBron James (Yes)

- 2009-10: Kevin Durant (No) and LeBron James (No)

- 2008-09: Dwyane Wade (No) and LeBron James (Yes)

- 2007-08: LeBron James (No) and Allen Iverson (No)

- 2006-07: Kobe Bryant (No) and Carmelo Anthony (No)

- 2005-06: Kobe Bryant (No) and Allen Iverson (No)

During the last fifteen seasons, only 26.7% of either conference final series has sported one of the top-two finishers in points per game in the same season. Admittedly, this isn’t the largest sample there is, but it disproves that having one of the top-two volume scorers in the league guarantees a deep Playoff run. We’ve actually seen more of the opposite; teams seem to be more likely to appear in the conference finals without, say, a thirty points per game scorer. This isn’t to say a team’s leading scorer hurts his team (although he sometimes does), but that a dominating half-court “assassin” is not a prerequisite to a deep run in the postseason.

Defensive Ignorance

With the current state of information available at the hands of most, there was bound to be a lopsided partiality to offense compared to defense. Box scores will track the number of points, rebounds, assists, field-goals, and turnovers a player records in a given period, but defense is restricted to steals and blocks (personal fouls are usually associated with the defensive box score but also include offensive fouls). Nagra is no exception to this tendency, expressing a clear opinion in Episode 34 of his podcast, which covered the validity of the terminology given to “two-way players.”

He immediately provides insight on how he distinguishes the best players:

“You know, the foundation of this game, since day-one, will always be scoring. The defense, all that other stuff is a bonus.” (Ekam Nagra – Episode 34 of the “Ball Don’t Stop” podcast)

As discussed earlier, this relates to the connection Nagra established between scoring on the team level with individual scoring on the player level. We have already concluded this connection is mostly false and overlooks the larger expanse of offensive contributions that leads to scoring output among teams, so it’s safe to say this mindset is setting up all further opinions that build on this principle for some level of failure.

However, it seems the prioritizing of high-volume scorer extends further than the structure of the game Nagra lays out:

“The most feared thing in basketball, till this day, is a guy that can walk into a game and effortlessly get you thirty, forty, and fifty [points].” (Ekam Nagra – Episode 34 of the “Ball Don’t Stop” podcast)

—

“I’ve never seen a coach break his clipboard because of two-way players just being a two-way player.” (Ekam Nagra – Episode 34 of the “Ball Don’t Stop” podcast)

—

“You know, those are the guys [scorers] that people remember forever…” (Ekam Nagra – Episode 34 of the “Ball Don’t Stop” podcast)

The common denominator of each sentiment is the reactivity to surroundings, especially emotionally-driven ones: fear, anger, and remembrance. Yet, Nagra uses these elements to evaluate on-court impact. The individual perceptions of these game actions may not even roughly correlate to value as a player, but he continually treats them otherwise. This relates to my earlier inferences that suggest Nagra structures his knowledge of basketball around his experiences as a player. However, as we explore later, having played basketball at even the highest level does not guarantee a higher ability to evaluate players.

During the same segments, Nagra explores what he believes to be an inherent disparity between offensive and defensive contributions, the former of which drastically outweighs the latter:

“Carmelo Anthony on the Knicks… top-four player in the game. You know, I didn’t care if he played defense or not. The fact that he could walk into a game and singlehandedly change the outcome, and… you know, have an impact on the game with just his scoring ability – that right there is it for me.” (Ekam Nagra – Episode 34 of the “Ball Don’t Stop” podcast)

—

“Hey, if you’re a good defensive player, you’re a good defensive player. If you can score the hell out of the ball, you know, you’re a killer, you’re an assassin out there.” (Ekam Nagra – Episode 34 of the “Ball Don’t Stop” podcast)

—

“You know, Michael Jordan and Kobe Bryant were the same way [skilled on offense and defense]. Like, I never saw anyone dub them as ‘two-way players.’ They were just the best players in the game… Them playing defense was a bonus.” (Ekam Nagra – Episode 34 of the “Ball Don’t Stop” podcast)

Defense is consistently treated as a secondary trait, a bonus, to offense. Nagra suggested no other skill in basketball matters if, at the end of the day, the ball wasn’t going in the basket. He doesn’t hold this to be self-evident; rather, the rules of basketball (which require a bucket to be had) make it so. This is more antithetical to how basketball is played than Nagra gives credit for. Through the entirety of his segments that cover scoring or defense, he doesn’t address that the magnitude of a two-point basket on offense is equal to that of a two-point basket allowed on defense. If the world’s greatest offensive player is worth 1.3 points per team possession but allows 1.3 points per possession on defense, he’s not helping his team win at all!

“Correctness”

The last revealing quotation from Episode 34 comes with his disagreement on the soundness of dubbing “two-way” play:

“What the f*ck is a two-way player? Like, who came up with this concept? You know, if you look back at it, like… I never heard this in the ‘90s. I never heard this in the 2000s.” (Ekam Nagra – Episode 34 of the “Ball Don’t Stop” podcast)

Nagra displays a clear bias toward styles of basketball that align with the styles of play that were most prevalent in his youthhood, with a strong emphasis on jump shots. During Episode 36, he provides this excerpt on a tendency he observed upon LeBron James’s arrival in Miami:

“I didn’t like it when he [LeBron James] went to the Miami Heat and he was like, ‘Hey, I’m not gonna shoot threes anymore; or, I’m gonna shoot less jumpers.’ … I didn’t feel like that was pure. You know, you can’t really cheat the game. You can’t be… like, it is what it is. You gotta make jump shots. In basketball, the foundation is ‘get a bucket,’ score a jump shot, all these things. You know, they matter.” (Ekam Nagra – Episode 36 of the “Ball Don’t Stop” podcast)

During his discussion on why he believed Kawhi Leonard was the second-best player in basketball, Nagra heavily implies a “proper” or “correct” version of basketball exists that some of the league’s players have violated. He, again, refers to his foundation of the game (to get a bucket), the misinterpretation of which already dilutes the quality of any appendages, but then extends it to: “You gotta make jump shots.” To improve the team’s offense, it would be undeniably more effective for the unit to score fifty-five easy layups (if those were somehow available) than to score thirty, forty, or even fifty-four of the most difficult mid-range shots in league history. After all, the team that scores the most wins!

Nagra’s inclinations toward his most prized styles of play signal heavy biases, and ones that cloud the truth behind “effective” basketball play as ones that are flashy, memorable, and visually remarkable. Thus, I don’t immediately absorb the opinions he states as ones of proper consideration, rather ones driven by personal preferences that don’t relate to the “true” topic at hand, which makes these claims nothing more than opinions in a sea of truth and falsehood.

We’ll fast-forward to Episode 211 of the Ball Don’t Stop podcast, in which Nagra an All-Rookie and All-Defensive former NBA player in Josh Smith. When Nagra asks Smith what the latter’s reaction was upon the arrival of the analytics revolution, Smith replies with:

“It [the analytics revolution] felt weird because… you know, when you start playing basketball, you’re taught the game the right way. You know, like, you know, mid-range, layups, three-pointers, you know, like… getting your teammates the ball… You gotta start inside out.” (Josh Smith – Episode 211 of the “Ball Don’t Stop” podcast)

There’s a recurring theme in the “Ball Don’t Stop” podcasts that distinguish a “proper” way to play the game, one that paves the way for Nagra’s (and former players alike) distaste of basketball analytics and advanced statistics.

Authority

Among the pillars of traditional values stated earlier was the extreme value of having experienced the competitive and rigorous environment of professional or semi-professional basketball play. If such a trait doesn’t reside within the individual, he or she is automatically less able to discuss the evaluations of a player at a higher level.

During Episode 211, he interviews an All-Rookie and All-Defensive former NBA player in Josh Smith. Nagra wastes no time in expressing disinterest in the analytics revolution and modernized statistics:

“I feel like the game now, as talented as it is, as athletic as it is, they’ve [analytics and its supporters] kind of dumbed it down, the way it’s played, man; and like, it’s just weird to me.” (Ekam Nagra – Episode 211 of the “Ball Don’t Stop podcast)

As we’ll explore later, Nagra sees the analytics revolution and its associated forthcoming as having deteriorated the play of the game, crucial context for later excerpts. Smith follows later in the episode with his own take on how players approach analytics:

“As a player, how can you listen to a person that never played the game of basketball? ‘Cause most of those analytical guys… have never played a game of basketball, so they don’t have a feel of… what’s really going on… and time and situation and… the mental aspect of the game… You can’t put that in the analytics.” (Josh Smith – Episode 211 of the “Ball Don’t Stop” podcast)

Smith certainly doesn’t speak for all players, especially the recently-employed more familiar with the analytical setting (Smith played his last full season in 2015-16), but there seems to be some notable stigma towards the analytics departments of NBA teams among players. They feel, as few to none of the analysts were players themselves, the analysts are not as qualified to dictate the tendencies and playstyles of those that are or were experienced as NBA players. Smith said that the lack of hands-on experience prohibited analytics developers from comprehending and incorporating the necessary elements.

I’ve never played in the NBA, so perhaps there’s something that I’m missing, but no matter who you are or what your experience with basketball is, the exact same forty-eight minutes of play (barring overtime) is available to any and all who can watch. At the end of the day, all of the court actions that a player is involved in can be absorbed by an outside observer. Granted, the comprehension of these court actions is a skill, and one that requires great knowledge and practice; but the only aspect of the game that a non-player can’t directly recognize is the “mental” aspect: what flows through the players’ minds. The ability to experience these may add context to the triggers behind varying neurological patterns in certain moments; but as Nagra continuously states, victory is crowned by scoring more than the opponent. No aspect of a player’s impact is exclusive to former or current players.

As Nagra and Smith continue their conversation, the latter gives more of his thoughts on how analytics is changing the game and, more specifically, how it affects the NBA as a show business:

“It’s sad, because… I feel like it’s gonna eventually take… the ratings are gonna start going down because… like, the exciting part of the game was dunking on motherf*ckers… like, putting that sh*t in the rim, putting they *ss in the rim… It’s like, all these threes and layups and floaters and sh*t… It’s taking the excitement out of the game.” (Josh Smith – Episode 211 of the “Ball Don’t Stop” podcast)

Smith clearly connects his distaste of analytics to how it affects the style of the game, an aspect for which Nagra also expressed concern. It’s not unreasonable to say that the pace-and-space style of basketball spurred by analytics makes the viewing experience less exciting, but then again, analytics were not created to improve game ratings. Analytics were created to give players and teams the highest odds to win. Advanced statistics and impact metrics aim to quantify and structure a player’s or team’s impact, not either’s likelihood of increasing viewer count. Thus, I see Nagra and Smith’s concern with analytics as not only misguided but untrue to the nature of its creation. Advanced statistics are not boosters of the NBA as a show business; they aim to provide explanatory and predictive power to help players and teams understand what happens on the court and to improve for the future.

I went into this examination of “traditional” thinking with an open mind, even hoping to add a piece or two of its process to my own if I were to find the right evidence. Unfortunately, I don’t feel I’ve been given any more reason to revert to traditionalism given the alternatives (i.e. analytics). Nagra does not speak for all traditionalists and Smith doesn’t speak for all players, but the brief taste I had of their ideologies was nothing more than unimpressive. They aspire for a desirable style of play that, along with the growth of data and information, became obsolete. Now, there’s certainly nothing wrong with deprecating the current style of play as it pertains to the watching experience, but the same practice in evaluating players and teams is a method doomed for failure.

Nagra peddles the belief that experience, or the lack thereof, is the problem in today’s game. To me, it’s less an issue stemming from experience, but the unrelenting tendency to hold onto ideals and the inability to adapt to an evolving game.