This is the first season for which I’ve done the Retro Player of the Year project, but it’s worth noting this isn’t the NBA’s inaugural season. That was actually the 1946-47 season, in which the league was known as the Basketball Association of America (BAA). For a myriad of reasons, but mostly related to the breadth and depth of statistical information, this was the cut-off I chose. Plus, although they’re uncommon, this way I had to deal with fewer instances like the Fort Wayne Pistons on November 22, 1950. I also could’ve chosen 1956-57 as the cut-off due to stabilizing talent distributions, but that felt too arbitrary. For now, let’s stick with the shot clock as successor to NBA “pre-history.”

The state of the league

First, let’s clarify a few things about the state of league, so that we’re in a better position to discuss the sport’s original greats in context. We’re still working with a primitive box score. Minutes weren’t tracked for teams. Steals, blocks, and turnovers weren’t tracked for players. Rebounds had also yet to be split between offensive and defensive boards. But otherwise, we’ve got a decent haul of points, shots, assists, rebounds, and fouls to work with.

The other major sphere of disparity between the classic and modern games is the rulebook. I’ll highlight a few of the major differences, and will likely refer to many of them in later seasons. Here are the ones worth considering now, and how they affect (based on observation and theory) the strategy and style of the early shot clock period:

- Illegal defense: The NBA outlawed zone defense in the winter following the league’s inaugural season, and wouldn’t overturn this rule for another fifty-four years. This had major ramifications for the spacing of the floor, how defenders operated away from the ball, and how teams strategized to score closer to the basket.

- No threes: This is an obvious one. While primitive jump shooters etched an extra groove into their legacies with innovation, outside shooting and spacing weren’t as pressing back then as they are now.

- Twelve-foot lane: The league wouldn’t re-widen the lane to sixteen feet until 1964, so for this nine-year stretch of basketball, there was even more emphasis on post play and crowded paints! Historians, anecdotes, and others seem to attest to this.

The closest thing I could find to on-court footage from this season was this video, covering what looked like the highlights of the seventh game in that year’s NBA Finals. While it’s no basis on which to establish the tendencies of individual players, we can hopefully make inferences about how the game was played. Let’s turn to the tape:

Based on this video, I’d infer the sport was barely evolved on the horizontal plane. You can see as early as the second clip (0:21), as the offense runs a traditional pick-and-roll, there’s one defender at the level of the screen. Not only is the screen poorly-set (watch the screener’s back fold when he makes contact with the defender), the defender’s instinct is to jab at the ball-handler (who’s several feet away) without freeing himself. (This isn’t to slander this particular defender, as he does a good job of chasing the opposing guard later in the possession.) We see this repeat in multiple possessions; although, if you’re optimistic, you could explain it as a reluctance to expand your defensive zone. There was no incentive to defend farther away from the basket without a three-point line!

While the sport was obviously post-oriented, the breadth of attacks wasn’t as robust as it is today. I’d have said the second thing that stood out most to me was the lack of baseline activity. Much of these plays were pick-and-rolls and feed-ins to big men who could score with their backs to the basket. Lots of the swirling cutters—and the defenders they pulled in their paths—were attacking the basket head-on. This could relate to the absence of the corner threat, but it didn’t appear players were regularly exploiting lapses in backline rotations among defenders. The shape of the court in this manner, however, could just as easily be associated with the narrower lane. Passing also wasn’t as advanced of a skill, so it likely wasn’t reasonable to camp out in the dunker’s spot and wait for lobs.

The most advanced (by both tactics and skill) pass in the video was thrown by Dolph Schayes, a behind-the-back pass out of a stationary post-up to a cutter. Re-affirming the primitive horizontal game was the defender of the other big stationed in the paint, who was inattentive to the cutter’s movement as it unfolded. You could say that’s a major theme of the older game’s spatial dimensions. The court was functionally half the size it is now, so “court coverage” and “roaming” were likely not as valuable, nor were they likely treated as valuable among the league’s defenders. But in the instances an off-ball cutter could attack (even if head-on) open space, both passer and receiver were generating easy points for their offenses.

How valuable were the best players?

There’s a pattern in NBA history in which the league’s talent distribution tightens during periods following expansion. For the most part, yearly standard deviations in Simple Rating System (SRS) are between 4 and 5.5 points; in the 1954-55 season, this was a measly 1.5 points. My guess is the likelihood of winning a title (prorated to a thirty-team league) this year to have been nearly twice as difficult than a typical non-expansion season. That means players who were able to separate themselves from the pack were even more impressive relative to season, and their marks in Ring Shares will reflect it! Based on team ratings, the implied spread of offensive or defensive value among players was not only compressed, but also fairly even, meaning we’ve yet to move into the period of disproportionately titanic defensive play.

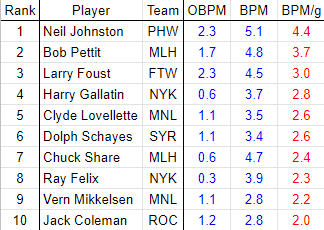

This version of Box Plus/Minus (BPM) uses estimators for the statistics that weren’t tracked (such as steals, blocks) as discussed earlier. This way, we could have a loose approximation—more robust than a metric like Win Shares—to understand how players provided value in previous decades. Listed above are the top-10 players in BPM impact per game (context-dependent, sums to team ratings) in the regular season. If you’re curious, the metric’s top offensive player (by far) was Bob Cousy (+3.0) of the Celtics, while the top defensive player was Chuck Share (+4.7) of the Hawks. Neil Johnston (+5.1) led all qualifying players in overall impact.

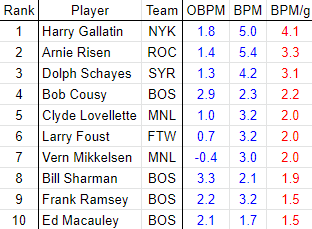

Based on the distributions between the regular and postseasons, players weren’t drastically upping their impact in the Playoffs. Listed above are the top-10 players in BPM impact per game (context-dependent, sums to team ratings, relative to all playoff teams, not matchups) in the second season. Boston carried its league-leading offense in the regular season to the postseason, and sported arguably the two-best offensive players in basketball in Bob Cousy (+2.9) and Bill Sharman (+3.3), while the defensive side was dominated by Vern Mikkelsen (+3.4) of the Lakers and Harry Gallatin (+3.2) of the Knicks.

Who were the standout players?

For my money, Bob Cousy was the best offensive player this year. Known for his razzle-dazzle style, an innovative combination of dribbling and passing, he was likely basketball’s most prolific shot creator. He had a reputation as one of few playmakers in the sport capable of consistently hitting his teammates for layups; and he was called the Houdini of the Hardwood for a reason! His display and technique were almost magical with the ways he’d guide the ball while barely flexing his wrist. From later footage, we can also discern he had a mildly effective jumper, and his overall scoring efficiency was higher than average this year.

Defensively, he was likely a negative, limited by size. Boston’s excellent offense was actually dragged down by mediocre defense to the point at which they didn’t even outscore their opponents in the regular season. But his estimated steal rates were better than average, and he was near the bottom of the league in fouls, which weakly reflects the superb hand-eye coordination that made him one of the game’s best passers.

Perhaps because of the fledgling tactics of the time, and because fewer teams in the league meant more familiarity with one another, statistical changes weren’t as drastic as they are today. Cousy’s scoring and passing statistics in 300 playoff minutes were right in line with his regular season averages. His rate of free throw attempts dipped in the Playoffs by about 2 per 100 possessions, but it’s worth noting these came in two series against the two-lowest fouling teams (Knicks and Nationals) in the regular season.

Dolph Schayes—who we just watched sling a behind-the-back pass nearly seventy years ago—was another player with a smoother stat retention in the Playoffs. He described his offensive approach as something similar to what you’d see nowadays: a big man whose threat to shoot would draw defenders out of the lane, after which he’d attack the rim and draw fouls. This is corroborated in his stat sheet, in which he was near the top of the league in free throw rate, and arguably the best at drawing fouls in that year’s Playoffs. Based on his efficiency, it was unlikely he was in the uppermost echelon of scorers; after all, you can only churn so much value out of primitive spacing, and a shot diet that’s heavy in jumpers could suppress True Shooting percentages relative to other bigs.

His passing (as demonstrated on sparse film and via assist rates) and long-range shooting at his position could easily be considered futuristic, but I’m unsure whether that necessarily made him one of the very best offensive players this year. He was comfortably the best option on that Nationals team; and while I struggle with considering this point too heavily, the Syracuse team was a below-average offense in both the regular season and the Playoffs that year. So while you can point to Schayes for paving some of the way for the evolution of the big man, he was likely a generation too early for that offensive package to exert all of its futuristic value.

There’s little to learn about Schayes’s defense. DBPM pegs him near the top of the league in regular and postseason; and even though rebounds were likely more reflective of defensive value this year than it is nowadays (Schayes was second in rebounds per possession in the Playoffs), I wonder if the numbers overstate his impact. He stood out the most among his bandmates, though fellows Red Kerr and Early Lloyd weren’t too far behind in dominating the boards. But since we’re working with so few measuring sticks here, and I see no reason to believe Schayes’s defensive portfolio is hollow compared to his teammates, my best guess was that he was a pretty positive on that end. And unlike offensively, Syracuse was the best regular-season defense and near the top in the ‘offs.

Harry Gallatin is one of the lesser-known Hall-of-Famers in Knicks history, and stacked up well next to Schayes. They had similar marks in BPM as defensively-slanting and providing massive rebounding value. But it’s very likely that Gallatin was more limited as an offensive player. His career isn’t super well-documented, but it’s known his status revolved around his immense physical strength, which allowed him to ascend to top-of-league status as a rebounder; and he was sturdy enough to be known as one of the era’s iron horses. Next to Schayes, he was a notch below as a scorer, albeit on above-average volume and efficiency. He was drawing fouls at a high rate (8.9 free throw attempts per 100), which actually carried over to the Playoffs at an identical rate. His assists rates were also slightly behind; but unlike Schayes, we have no way to qualify his passes. Either way, he seems to have more positive than negative traits on that end.

The Knicks were at the top of the league in rebounds and near the bottom (in the good way) in fouls, but weren’t clearly an above-average unit. Does this add to the suspicion that the team didn’t roster a true defensive stalwart? And to what degree does that contextualize Gallatin’s stats as the team’s leading rebounder despite not being the center? Ray Felix, the team’s center, struggled in the team’s playoff series and their overall efficiency plummeted. Is this evidence that Gallatin was something closer to a peripheral defender than the centerpiece that his box scores suggest? Either way, he’s clearly a strong value-add, and I think we can make educated guesses about his defensive makeup: helping off opposing fours, boxing out, and cleaning up the boards to allow the true big to focus on defending post-ups.

| Player | DBPM change | Team DRtg change |

|---|---|---|

| Ray Felix | +0.1 | 10.1 |

| Harry Gallatin | -3.9 | 10.1 |

Ray Felix, meanwhile, was an impressive player on both ends of the floor—a volume scorer on good efficiency was a monster on the boards. Based on height, positions, and the traditional style of play, I think we can reasonably assume he was analogous to the anchor of New York’s defense this year. However, as we discussed with Gallatin, these units were mediocre in the regular season and underperformed in the second season. (Unfortunately, I’m bound to emphasize team-level results with such limited tools to work with.) There’s limited documentation of his career as well, so we’ll have to base our inferences on his scoring, limited passing (based on assists), and infer his role from there.

Bob Pettit made an immediate splash by capturing the league’s Rookie of the Year; and by my count, actually led the league in scoring rate. He was quickly integrated as a power forward and sported another one of those innovative jumpers. Later in his career, his cerebral style of play included head-on cuts, slips behind defenders, but it’s an unknown how much of this he could have done, given his dramatic weight changes. Paired with strong rebounding and an above-average team defense, there’s no indication he was a below-average defender. He doesn’t have a reputation as a defensive stalwart, but his eagerness to rebound and the sole footage we have demonstrates a keen awareness and activity in the post that’s likely providing positive value. My question is whether he’s on the level of, say, Felix or Gallatin, who both appear to be quite large positives on that end.

Neil Johnston was in the upper crust of the league’s scorers and a considerable defender by available measures. His Warriors didn’t make the Playoffs this year, but based on postseason changes among big men with similar reputed styles and statistics, it’s unlikely Johnston would have been a playoff “faller.” He had airspace between himself and the next player on my BPM leaderboard; so based on that, he comes across as an early candidate for the season’s best player. The only cause for concern in his profile is the Warriors’ mediocre efficiency, but the surrounding roster doesn’t justify much penalization. Paul Arizin was the team’s next-best player, and he clearly needed time to break in after returning from military service in the previous two years.

The title of the league’s best scorer this year might have belonged to Larry Foust. Despite eight All-Stars and two All-NBA’s during his career, he surprisingly missed the cut as a Hall-of-Famer, so this is another primitive star for whom we have to infer style from how he seems to stack up next to teammates. He was an efficiency monster in the regular season, but dropped off in two playoff series against teams with strong low-post presences (Mikkelsen and Schayes). During this time, his assists increased significantly, but on more true shot attempts. Fort Wayne’s offense improved in the Playoffs, so it’s worth entertaining the idea that more of Foust was a good thing, although you’d have to distribute that kind of credit unknowingly among teammates Frankie Brian and Dick Rosenthal for similar reasons.

We haven’t even gotten around to the Minneapolis Lakers yet! Based on my BPM, they actually sported two players with cases near the top of the league in the aforementioned Vern Mikkelsen and Clyde Lovellette. Lovellette’s offense was known to shift between the style of a wing or a big, with his signature move reputed to be the one-handed set shot. That scoring versatility—despite a virtual absence of playmaking—made him a clear offensive value-add. Minneapolis’s defensive stud, however, was Mikkelsen. Like Gallatin, was known for dominating strength and rebounding ability, to the point at which opponents used stalling tactics to keep the ball out of his domain. If we’re to put the duo into modern terms, Lovellette was the rover to Mikkelsen’s centerpiece.

The Ranking

Ah! Time for the fun (excruciating) part. I’m obviously far less confident in how I’m going to arrange these players than if I were to do it, say, for the most recent season. Due to our measuring limitations, this is pretty much an anecdotal, box list—not to say that it’s completely devoid of an analysis sufficient to rank. But I want to emphasize how much wider the confidence intervals are. My original plan was to go down to tenth, but the lines were eventually too blurry. Based on everything I just discussed, here’s my top-5:

- Neil Johnston [0.18 Ring Shares]

- Dolph Schayes [0.14]

- Bob Pettit [0.09]

- Vern Mikkelsen [0.09]

- Harry Gallatin [0.08]

I’m slightly more comfortable with Pettit and Mikkelsen higher than Gallatin; but realistically, anything past the third spot is up for grabs. Foust and Cousy were actually tied with Gallatin for the fifth spot (meaning Gallatin is my gun-to-the-head pick). I could easily be talked into sliding Clyde Lovellette into the back of the list. I’d also entertain an argument for Milwaukee’s Chuck Share, but his career is so under-discussed it’s difficult to establish a position for him.