Basketball is one of the most divisive sports in how its followers interpret the actions and results of the games. Enough of a mixture of ambiguity and clarity exists that allows viewers to, depending on their psychological tendencies, to either hold very assured or very doubtful opinions. Although the following is not a trend of any large population, in my own experience, I’ve frequently felt less confidence in my assertions as the quality of my research on a particular topic increases. This isn’t a knock on any type of analytical method; rather, over time, as I’ve learned more and more as to what information is worthwhile and which conventions aren’t, the insurmountable number of hindrances that prevent “correct” conclusions becomes more and more obvious. That’s why, without a proper framework to assess certain aspects of the game, a lot of the givens and guarantees set forth by critics and fans are doomed for failure.

Thinking Basketball was an invaluable read that does justice to its description: “a guide to being a responsible fan.” I was already acquainted with a lot of the concepts discussed in the book, yet it was nothing short of an eye-opening experience. It provides value from a psychological perspective, having been written by Ben Taylor, a cognitive scientist in addition to an NBA analyst. The self-proclaimed subtitle of the novel, per Taylor’s website, Backpicks, stresses “‘…Why our minds need help making sense of complexity.’” A foundational idea in the book is how the human brain is unable to properly categorize and store the hundreds of thousands of court actions from the tens of thousands of possessions that occur in an NBA season, and how negligence of that paves the way for a multitude of unconscious biases and misconceptions that dominate commercial and media analysis.

This is a large reason for my skepticism of heavily eye-testing games. Unless the viewer is able to watch every single one of a player’s possessions over the course of a season, a lot of that “mental extrapolation” doesn’t act as a very representative picture of a player’s tendencies. Even if someone managed to watch every single possession, they’d also have to overcome faulty memory, which would require an extremely diligent note keeping system. Not even that guarantees “correct” representation, as the viewer needs to also be able to identify the causal actions of a play rather than the outcome alone, a skill that is surprisingly rare.

The concluding sentence of the previous paragraph is very significant in my emphasizing how important Thinking Basketball and its ideas are. The large majority (an understatement) of critics and fans are not aware of the biases and misconceptions that riddle their inferences, thus hindering the growth of these principles. I’ll return to the possibility of what may be the necessity for the continuation of the incorporation of these obstructions later, but on an individual level, the absorption of the techniques presented in the book will work wonders for the unexpecting reader. I’ll discuss the fallacies introduced by Taylor that pertain to certain examples I’ve encountered to, hopefully, give reason to purchase Thinking Basketball and consider its contents.

Scoring Blindness

It’s no secret the mass usually sees the “best” players as the best scorers. After all, if the player is managing to put the ball in the basket, he’s probably doing something right. This is hardly the case. Without delving too deep into the phenomenon that is “scoring blindness,” it’s simply the widespread propensity to overrate the effects of “individual scoring,” measured by statistics such as points per game and scoring rate. This causes a player who provides significant value in other aspects, such as creation and defense, to be disproportionally valued against the leading scorer on the same team, who might actually be hurting the offense’s efficiency depending on the circumstances.

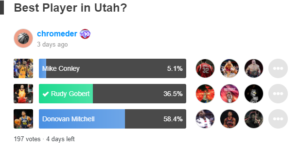

The perfect modern example of how “scoring blindness” influences opinions lies in the current Utah Jazz, a team that features an ostensible race to be named the team’s best player between All-Stars Rudy Gobert and Donovan Mitchell. Any fan who’s paid even minor attention to the league in the past three years knows Gobert as the defensive titan who anchors Utah’s annually good team defenses and Mitchell as the volume scorer who acts as the Jazz’s offensive commander. Last week, I issued a poll on Hardwood Amino that simply asked the voter to choose which player they thought was the “best” in Utah between Mike Conley (an outside candidate), Gobert, and Mitchell. With 197 votes tallied, here are the results at the time of this writing:

The application allows the user who issues the poll to vote, which is needed to view the results. The green check denotes the player for whom I voted.

Even with my extra vote for Gobert, nearly sixty percent of participants saw Mitchell as the best player on the Jazz. This doesn’t necessarily mean the same proportion of the population feels the same way, but perhaps this signals the potential trend that would be in favor of Mitchell. I was able to gain insight from a “Mitchell supporter,” @paydaypayton (whom I’ll refer to as “Payton”) on Discuss TheGame, in an earlier discussion. A portion of his argument in favor of Mitchell relies on the following viewpoint:

“But we [are] really forgetting that Mitchell has been basically single-handedly the reason why the Jazz have had any success in the postseason…”

Payton may reminisce on this statement as a hyperbolic response, but let’s explore the possibility of Mitchell as, at the very least, the primary driver of Utah’s success in the postseason. Measurements I lean towards as painting a strong picture of a player’s per-individual-possession value to his team is the Oliver Rating System, typically referred to as Offensive and Defensive Ratings, which estimate the number of points a player produces and permits on either side of the ball per 100 individual possessions. Because no player is involved in 100 team possessions a game, these ratings can seem outlandish, but are, in fact, great estimates on the basis it uses – individual possessions.

The portrayals of either player from Oliver’s ratings, which I happen to agree with, are that the very different styles of offense they play generate different results. Gobert, due to a healthy 78% of his field-goal attempts in the Playoffs coming within three feet of the rim, a high frequency of offensive rebounding, and low-risk offensive possessions, generates considerably more points per individual possession than most players (this is a large reason for Oliver’s emphasis on roles when using his ratings). Thus, it’s not abnormal to see his marks in this stat remain higher than Mitchell’s quite often. Truth be told, he generated more points per individual possession in every one of the Jazz’s last three Playoff runs. But, because this may yield more of an apples-to-oranges comparison than we’re hoping for, we also have to consider Mitchell’s role in improving Utah’s offensive efficiency.

During the Playoffs, Mitchell doesn’t usually yield a highly-efficient style of offensive play. His rookie campaign, one marveled for its “achievement” of dethroning two All-NBA players in the first round (Paul George and Russell Westbrook), produced a measly 1.01 points per individual possession in the second season. Relative to the league average of 1.09 points per possession in 2018, Mitchell wasn’t truly helping his team succeed in the manner Payton suggested. Per Synergy Sports Technology, Mitchell averaged the sixth-most isolation attempts per-game in the 2018 Playoffs. However, unlike great and high-volume isolationists, Mitchell’s offensive play didn’t net many points. As it turns out, he was actually hurting Utah’s offense more than he was helping it. Mitchell’s isolation attempts yielded a woeful 0.95 points per attempt. If Utah replaced its entire offense with his postseason scoring “heroics,” they would have sported one of the worst Playoff offenses in league history.

The trend carries over to an even less successful run in 2019 that saw Mitchell produces a putrid 82 points per 100 individual possessions. Namely, if the above scenario were invoked again: if the Jazz allowed Mitchell to captain the entirety of the team’s offensive possessions (keep in mind the offensive rating measurement does not account for any late-game fatigue), they would very likely have the most inefficient offense in league history, when his isolation output made the ugly drop to 0.75 points per possession on only one fewer attempt per-game. The only season that defies this trend was last year’s first-round series versus the Denver Nuggets, in which Mitchell’s scoring numbers finally exploded. He averaged an incredible 37.8 points per 75 possession on a True Shooting percentage nearly 13% greater than league-average. He also averaged 1.11 points per isolation possession, a massive improvement from his previous two postseasons. What spurred this seemingly inexplicable change?

Variance

The widespread solution, one likely employed by those similarly-minded to Payton, is that Mitchell had a “scoring epiphany” of sorts that allowed him to “finally figure things out.” To treat Mitchell’s scoring burst in the previous Playoffs as an accurate representation, or even an adequate signal, of his true scoring abilities would be a product of multiple fallacies, all of which are explored in Thinking Basketball. The first relates to the time span in which Mitchell produced these numbers, a mere seven games, against a mediocre defense for that matter (Denver had the #16 ranked defense in 2020). Since the duration of Utah’s run was only seven games, it’s supposed to feel like a sufficient representation of Mitchell’s postseason value, except it isn’t. The second bias present relates to variance. Because Mitchell’s averages were notably good in the series, it’s easy to overlook the negative aspects in that timeframe.

He had arguably his best game in the series in Game 1, which saw him score a mind-boggling 57 points en route to a 45.1 Game Score, a composite metric that numerically evaluates a player’s performance in a game. Keep in mind, however, that Game 7 of the same series saw Mitchell score a dreadful 4.5 score in the same metric, scoring only 22 points as opposed to an average of 36.3 points-per-game in the series. The lesson to be learned from this case is that a large number of unexpected, unattainable leaps in numbers that will never be reached again by the same player are products of variance. Mitchell, given eighty-two games versus the exact same Denver roster, in the same setting, alongside the same teammates, and maintaining the same level of “true” value, would have seen his points-per-game fall much closer to his regular-season average of 24 points-per-game.

Due to the prior information we have on Mitchell, addressing these numbed biases shows that he wasn’t “truly” the league’s best scorer in the postseason. Rather, he was one in a long line of players whose degree of variance in the right timeframe creates the illusion of boundless leaps in talent. Further fallacies with Mitchell’s title as Utah’s best player include the “Lone Star Illusion,” the unsound mitigation of supporting cast efforts to divvy team credit, which I’ll address later on. My goal with this and future posts in the series is to update these communities with their unconscious biases, ones no one is immune to, and hopefully tease out the internal questioning we all need. To everyone reading, and especially Payton (!), I encourage you to add Thinking Basketball to your reading list.

Leave a Reply